Learning how to write a memoir is like studying to be an archeologist. Not only do you have to dig deep and sift through the sands for fragments of the past, you then have to piece it all together and discover what the story is. To help you tell a compelling story based on your own life, we turned to bestselling ghostwriters on Reedsy to create our practical guide on how to write a memoir.

- How To Write A Memoir

- Writing My Memoir

- Writing My First Memoir

- Help Writing My Memoir

- Writing My Memories

- Memoir Steps

Writing memoir can be revealing, personal and therapeutic. It helps you learn from the past, and sometimes it helps you heal as well. Memoirs are short and mid-length books that describes particular portion of your life. My Memoir is a platform that focuses on this particular genre of writing. Writing a memoir isn't for the faint of heart. As you're learning the craft and technique of memoir, you're also reckoning with your life. And oftentimes, the place you end up isn't where you began. Despite that, writing your memoir can be an incredibly rewarding journey—one that allows you to move into a deeper sense of self.

Step 1. Understand the market

Writing a memoir can take months (if not years) of your life. To cut down on your chances of disappointment down the road, you need to know what you’re writing, and for whom.

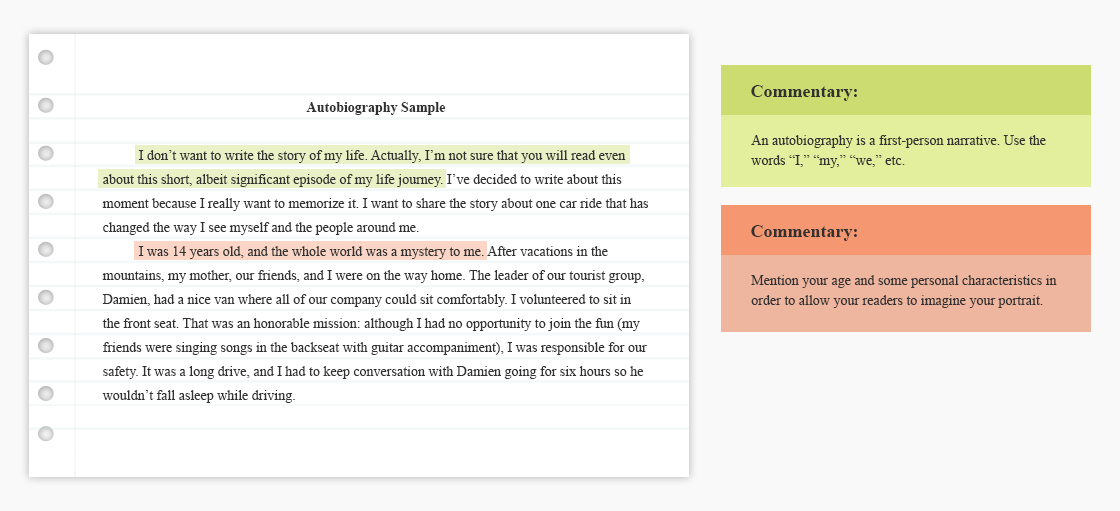

First, make sure you’re completely clear about what a memoir is, and how it differs from an autobiography. Then, figure out where your book fits within the existing market.

Memoir publishers are looking for books that will resonate with a wide range of readers. If they don't think there's a strong market for your book, an editor won’t take the chance — regardless of your manuscript's quality. Acclaimed ghostwriter Katy Weitz suggests researching memoir examples from several subcategories to determine whether there’s a readership for a story like yours. Identifying this target market will go a long way towards convincing an editor of your memoir's potential.

A great way to start your market research is with the first two posts in this series: What is a Memoir? and 21 Memoir Examples. Take a look before moving onto step two.

Of course, not everyone has their heart set on a traditional book deal. After all, shifting copies isn’t the only reason to write a memoir. Perhaps this is something you want to do for yourself, or for your friends and family? This kind of memoir is known as a legacy memoir: intended for a more limited audience, they help writers to recall and cement the memory of a certain time in their lives, or to leave behind important stories and lessons for their family.

Step 2. Write a book proposal

If you want to sell your memoir to a traditional publisher, bear in mind that you will have to, at some point, submit a book proposal. As well as providing details about the target market and your book’s place within it, a proposal will also contain a chapter breakdown of your memoir.

Some authors will work with a ghostwriter to write their book proposal, even if they end up writing the manuscript themselves. Not only do they benefit from the ghost’s understanding of the submission process, but they also benefit from the interviews that are conducted, as well as their guidance in structuring a compelling memoir.

Working with ghostwriters on a proposal is significantly more affordable than a full ghostwriting project — it’s a great way to get the input of a real professional without breaking the bank to get them to write it. This may be a good middle-ground option.

For more advice, read our guide to writing an effective book proposal.

Step 3. Interview yourself as a journalist would

Take the lead from authors like award-winning ghostwriter Sharon Barrett. That is, get under the skin of your subject: you.

“I’m ghostwriting for a successful businessman who wrote his own memoir a few years ago. He wrote a perfectly fine narrative, but it was impersonal because he didn’t know how to ask himself the questions that would allow him to dig deeper — to look at the events that helped shape him, what he sacrificed, what he learned. It’s an exercise in courage to go back through the years and take a hard look at the ups and downs, but it’s the only way to tell the true story.”

A memoir is like a diamond necklace: before you can set the stone and craft the chain, you have to extract the ore and refine it. As Barrett suggests, you should treat yourself as an interview subject and ask yourself questions that can trigger stories that may have slipped beneath the surface.

Step 4. Go the extra mile with your research

One of the realities that memoir writers inevitably face is that memory is mostly unreliable, according to Heather Ebert. “What you remember about past events may be empirically false, but they can still be emotionally true. That doesn’t mean all of your memories are wrong, but go into the writing questioning every memory and assumption you have.”

Here are a few of Ebert’s research suggestions:

- Investigate every story, fact, feeling, or vague inclination you have about your past insofar as it applies to your account.

- Look up anything that can be verified or fact-checked: World news, local weather, dates, places, events.

- Revisit locations and settings from the past that you plan on writing about.

- Interview your family members, friends, and others who were around in specific eras.

- Get your hands on photos from that period in your life — they might be family snaps or ones from a local newspaper.

- Draft a timeline of your life by year. Writing about a particular experience will pull up more memories as you open the floodgates.

- Don’t invent or make things up — especially not anything that can be verified (see Frey, James: A Million Little Pieces).

Once you've collected the raw material, organize these memories in a way that makes sense for you. Some writers like to mind-map, others might compile them into a scrapbook or paste them into a journal. Some sort of structure in your research will pay serious dividends when you actually start to write your memoir.

Step 5. Decide on your message or theme

For Carolyn Jourdan, an author and ghostwriter of multiple bestselling books, knowing the message is vital. “The best piece of writing advice I’ve ever been given was from a Professor. He said, “When you get stuck, ask yourself, ‘What am I trying to say?’”

By addressing a specific theme or a message, you will give yourself an intense focus that drives the story and what you do or don’t include.

“Your theme is the meeting point on which readers will relate to you and recognize themselves in your story. Your story may have several themes, but consider what you want the overarching point to be.”

For example, Elie Wiesel’s Night chronicles his experience in Nazi death camps. On a thematic level, however, it deals with questions of faith as the author grapples with the idea of a God who would allow such horrors to take place.

You might not start with a clear idea of what you’re trying to say. But through your research and interviews, you may begin to find that certain lessons or ideas keep popping up throughout your life. And once you discover the spine of your story, you’re off to the races.

Step 6. Collect your moments of high emotion

With your interview answers in hand, you will likely have too many stories to pick from. Which ones should you prioritize, and which ones should take a back seat?

“My approach might not work for everyone, but I always start with the moments of highest emotion,” says Jourdan. “I try to get as many of these moments as I can and build the book around that. When were you the most afraid, confused, euphoric, etc.? Those are the moments when you see the true character of a person emerge.”

Once you have your list of high-emotion moments picked out, you can see how to best use them to tell your overarching story and reinforce your message and themes.

How To Write A Memoir

Step 7. Grab the reader’s attention from the start

Eschewing strict chronology, many memoirs chose to open with a story from the middle or end of the narrative.

“Start with an incident that captures the central theme of the book as vividly as possible,” says ghost Johnny Acton, who has written for public figures such as Paul McCartney and Prince Charles. “Unless your birth was dramatic in itself (e.g., your mother was stuck in a lift with a group of Trappist monks), it's probably best to avoid beginning with it. Too obvious and clichéd.”

Potential readers will skim through the opening passages, either in-store or with Amazon’s Look Inside feature before they decide to purchase it — if your first few pages don’t grab them, they won’t buy it.

Step 8. Focus hard on detail and dialogue

This falls into the classic writing advice of ‘Show, don’t tell.’

“Remember to describe how you felt about things as they happened,” Crofts says. “Don’t go into too much description (no beautiful sunsets). In fact, keep adjectives and adverbs to a minimum, making the nouns and verbs do the heavy lifting. Keep detailed information such as dates and times to a minimum unless crucial to the story.”

Take the lead from your favorite writer (or writers) and see how they write narration and dialogue to play out their scenes.

“Use direct speech as much as possible,” Acton adds. “It doesn't have to be 100% accurate, it just needs to capture the personality of the speaker and the essence of what was said.”

With these steps in mind, you will hopefully have enough inspiration to work your way through the first draft of your memoir.

Step 9. Avoid the most common memoir pitfalls

As with any creative endeavor, writing a book about yourself comes with its own unique pitfalls. In this section, we'll look at a few of the most common mistakes.

Mistake #1. Making yourself a hero

There’s a scene in the British sitcom I’m Alan Partridge where the title character, a disgraced former TV host, is on a radio show to promote his self-aggrandizing memoir. It’s pointed out by a guest panelist that every anecdote in the book ends with the phrase, “Needless to say, I had the last laugh.”

While a book is often an opportunity to ‘tell your side of the story,’ don’t paint yourself as a complete hero or victim. Like any protagonist in a novel, it’s your strengths and weaknesses that will make you a compelling figure. Readers expect honesty and candor. If they sense that you’re stretching the truth or have an underlying agenda, they will quickly switch off.

Mistake #2. Choosing a strictly linear structure without considering the alternatives

“To help give order to the memoir, try to tell the story chronologically to start with,” says Andrew Crofts, the bestselling ghostwriter of over 80 books. “That way, you can keep control of the narrative. If you jump about too much, you will forget what you have already done and repeat yourself. You can always change the chronology at the editing stage.”

As Johnny Acton says, there are great reasons to chop-up the timeline:

“A broadly chronological structure will make the book easier to follow but don't adhere to it too closely. Flashbacks and flash-forwards can be used to add interest.”

Writing My Memoir

Taking a cue from your favorite novels, you may find that playing with chronology helps to control the pace of your books and cut out ‘the boring bits.

For more advice, check out our guide to outlining a memoir.

Mistake #3. Not getting an outside opinion

At some point, you might want to share a draft with a close friend or family member. Their feedback can be priceless, as they might remember events differently to how you've portrayed them in your book. Based on their reactions, you can choose to work in their suggestions or stick to your guns. However, it's also important that you get someone who doesn't know you to read your manuscript.

“Always remember that the reader may not know what you take for granted,” says Johnny Acton. Beta readers who don’t know you that well can help you see when your stories need more background information (and when they’re not compelling or relevant enough).

Professional editors are also an invaluable resource to tap into. On platforms like Reedsy, you can search for editors who have worked for major publishers on memoirs like yours. For those legacy projects, a professional editor can help you focus on the parts that matter; if you write something with a commercial edge, they can make all the difference when it comes to selling your book.

These are just a few tips that will help you get started. Along your journey, you may encounter well-meaning and highly qualified people who will question why you think you should be writing a memoir. But if you have a story that you feel needs to be told, you shouldn’t let anyone stand in your way. Everybody has a tale to tell: just make yours a good one, and the rest of us will come along for the ride.

by Kendra Stanton Lee

“All I have are Iggy Pop and dirt-biking before I got locked up,” one student shared with the class.

That sounds like plenty of material to me, I said, as I began to jot some of the student’s memories on the board.

First, I drew a large rectangle box in dry erase marker. I explained that this would be the core theme of what connects these memories — if, in fact, we found a connection. But first, we had to map out the time frame of the memories, the images that came from the memories, and the cast of characters present in the memories.

Extending from the main box, I drew spindly legs pointing in every direction.

“Each leg represents a singular memory, a slice of life,” I explained. This is the scaffolding upon which we build our work. This is how I help to usher my students toward the difficult work of memoir writing.

My student shared that he spent many seasons of his youth dirt-biking in rural areas with friends. He recalled some of the music that reminded him of these times. He also shared a specific memory of being chased by police officers because, he explained, these were not simply bicycles but rather motorized off-road bikes, not permitted on major byways, but that he and his friends dared to ride on the wide open road.

This particular student had experienced time behind bars and was in a pre-release program so that he could attend our class while he was serving the remainder of his sentence. As the student and I mapped out the memories of biking, police encounters, as well as his experience in prison, other students began to notice the themes. There were moments of freedom and childish shenanigans. There was also a price to pay for exercising these freedoms. Fun and frivolity can lead to crime and punishment.

It seemed that this student could better ascertain a theme — that of trading childhood for adulthood — from having shared the memories aloud, as well as seeing them written on a large canvas, with other classmates lending their own eyes and ears to the exercise. The student went on to write a memoir of which he was proud, threading in lyrics from various Iggy Pop songs that related to his story.

I have drawn a spiderweb on the dry erase board of so many college classrooms. Until I began working with a population of students largely from under-resourced neighborhoods, I never realized how powerful simple personal narrative exercises could be. While my students are mostly pursuing degrees in technical fields, many have shared with me that they never thought of themselves as writers until they attempted memoir writing. This exercise requires no prior knowledge of literature and does not require a mastery of language. It simply asks that the writer be willing to trace back to the people, places, and experiences that have shaped their lives.

“The spiderweb,” otherwise known as a non-linear visualization of interconnected memories and events from our lives, has been one of the most successful teaching methodologies in my English composition classes. I measure the success of this exercise by the number of students who have requested it, and how often they ask for extra worksheets as they are preparing to write their short memoirs. Semester after semester, students ask if I have any “extra spiderwebs.” This is not an original method by any means, but I find that my digital native students crave more tactile ways to work through their personal narratives. They scroll, scan, and swipe screens all day. The experience of pressing pen to paper, or scribbling on a big dry erase board, while not novel, seems to trigger something important for the students that they do not access in other spaces.

Writing My First Memoir

I teach at a technical institute in Boston where my students are mainly first-generation matriculants. Some have aged out of foster care and are learning to live independently for the first time. Others contend with poverty and the attendant instability that is so often part of the territory. Because of the instability and trauma many of my students have experienced, I take very seriously my responsibility as a teacher to shepherd them in writing their memoirs without triggering unresolved trauma.

The spiderweb knows some stories aren’t linear

An obvious approach to writing essays is to first identify a theme and to build a case full of evidence around that theme or thesis. But what if you’ve not yet processed the “evidence” of your own life? What if you have only learned to live with constant flux and the frequent need for flexibility, even around basic needs such as food, shelter, and clothing? Although I am not a mental health therapist, I know that processing our lives through writing can be helpful or hurtful. The spiderweb allows us to break down our thoughts and memories in a way that I hope is manageable for every student.

The spiderweb is a fairly rudimentary diagram of which I print a few copies for each student. I tell them that this is just for scribbling ideas down — nothing is in wet cement. First, I encourage students to try to think of a relationship or experience that was formative for them:

Is there a relationship that caused you to change your character or perspective?

Have you had an experience that changed your perspective on the world, or your opinion of yourself?

Did you work toward a goal and reach it or not reach it? What was that journey like and what was the destination?

Have you experienced something that friends often find interesting?

Once they have identified an experience or relationship that seems formative, I encourage them to write down memories in the “Memory” section at the top of the spiderweb. I remind the students that these memories may not seem exciting, but that they are still important—our memories may be trying to teach us something. The memories may be vivid or vague, and they can write down as much as they like. They don’t need to judge the memories, just to write down whatever comes to them.

Here is the basic form of the spiderweb:

We then try to identify the time frame in which the memories occurred, any sense memories (sights, sounds, smells) associated with the recollections, and the “cast” members that played major roles in these memories.

Once we look at our spiderwebs, sometimes students still feel lost about what the information represents. I tell students there is no need to rush to conclude anything, to draw any grand thesis statement. Sometimes they may want to walk with their memories for a bit, or to examine whether they see a pattern play out in other parts of their lives.

Even getting stuck, though, presents an opportunity with the spiderweb. Just as when one’s car winds up in a ditch, no one is getting that car out of the ditch by themselves. The same goes for our personal narratives. Sometimes we’re too close to the nature of our stories to see the metaphors and themes emerging.

When students get stuck

This is actually my favorite part of the exercise. I draw the spiderweb on the dry erase board and I invite a student to share with the class what they’re seeing emerge on their page.

In a recent class, one of my students shared that he was struggling. He felt bad about his memories. He loved his parents and knew they had tried hard in raising his family, but their early separation had been shattering for him. Yet, he didn’t want to shame his parents in his memoir. So I asked him if he would “reverse engineer” his memories. If he could start with his life today — how is his relationship with his parents now? Is there a recent memory that captures what the relationships are like? What does he hope for himself? That is, does he hope to have a family of his own one day? Then I encouraged him to work backward and to write down any memories of what it was like for him growing up with two different households, scrolling back to the day when he remembers his parents separating. I reminded him that this story was about him and not about his opinion of his parents. He was empowered to center himself in the action.

The student experienced a beautiful breakthrough and other students weighed in that they too knew what it was like to love their parents and also to have gone through family strife. The student said he had not written about his family before because he had feared assigning unfair judgment. By working backwards from recent history to deeper history, the student could be the protagonist of his own tale.

The final flourish in the spiderweb is when the students decide what their memoir is about. They write in the center of the memoir what they have concluded from what they have written upon the “threads”: their memoir is about them and their experience(s) — but mostly what they did as a result of those experiences. Using the spiderweb as our outline, the students are then better prepared to write their 2-4 page memoir in paragraph form.

The stories that have emerged have stunned me to breathless silence. One student who did not want to write his memoir, especially as it included his recent imprisonment, found one of the legs of his spiderweb was his devoted girlfriend. Writing about their relationship and the hope it sustained for him through his incarceration was uplifting for him, and he said it helped him to focus on the good in his life.

About the student who incorporated lyrics by Iggy Pop, a musical interest we both shared that I might not have known about otherwise, I truly believe the prolific songwriter himself may have known how I feel as the teacher of spiderwebs. I feel that I am both the driver of the vehicle, and once the students are able to access their threads, I become the passenger. To quote Mr. Pop:

“Oh, the passenger

He rides and he rides

He sees things from under glass

He looks through his window’s eye…

And all of it is yours and mine”

Help Writing My Memoir

What a joy it is to help students access the stories that have shaped their lives, and in this way, they consistently shape mine.

Writing My Memories

Memoir Steps

Kendra Stanton Lee is an instructor of humanities at Benjamin Franklin Institute of Technology in Boston. Her essays have appeared in The Washington Post, The Boston Globe, Slate.com and others. She lives with her husband, their two children, and a wily rescue dog.